Photo by Tom Fisk on Pexels.com Photo by Tom Fisk on Pexels.com |  Photo by Julius Silver on Pexels.com Photo by Julius Silver on Pexels.com |

When the Trump administration imposed tariffs on Chinese goods in 2018, the stated goal was simple: protect American manufacturing. But tariffs don’t work in isolation. They cascade through supply chains, altering prices, employment, and business decisions in ways that reach far beyond the targeted industry.

A small appliance manufacturer in Ohio might celebrate tariffs on Chinese imports. But that same manufacturer sources components from suppliers who now pay more for steel, aluminum, and electronic parts. Local retailers selling the finished products face higher wholesale costs. Consumers pay more, reducing their discretionary spending at nearby restaurants and shops. The tariff meant to help one business creates a ripple effect that harms dozens of others.

Every business is downstream of something

Modern supply chains are deeply interconnected. Even businesses that don’t directly import anything are affected when their suppliers face higher input costs.

Consider a local furniture maker in North Carolina. They don’t import furniture. They make it. But they buy:

- Lumber (possibly tariff-affected if it’s Canadian)

- Hardware and fasteners (likely imported)

- Foam and fabric (often tied to imported petrochemicals)

- Tools and machinery (often imported)

- Delivery trucks (tariff-affected steel and aluminum content)

Each tariff increases costs somewhere in that chain. The furniture maker can absorb the cost (reducing profit margins), raise prices (reducing sales), or cut costs elsewhere (potentially reducing quality or employment). None of these options help the local economy.

Import-competing businesses win, but import-using businesses lose

Tariffs benefit businesses that compete directly with imports. A steel mill in Pennsylvania benefits when tariffs raise the price of imported steel, making domestic steel more competitive.

But for every steel producer, there are dozens of steel users: automakers, appliance manufacturers, construction firms, machinery producers. When steel prices rise, these businesses face higher costs. Some will relocate production overseas to avoid the tariff. Others will automate or downsize. Many will simply pass costs to consumers.

Research on the 2018–2019 tariff waves finds higher input costs and negative downstream impacts, including weaker employment outcomes in more exposed manufacturing sectors.[1]

Consumers always pay

Tariffs are taxes on imports, and like most taxes on goods, the burden shows up in domestic prices.

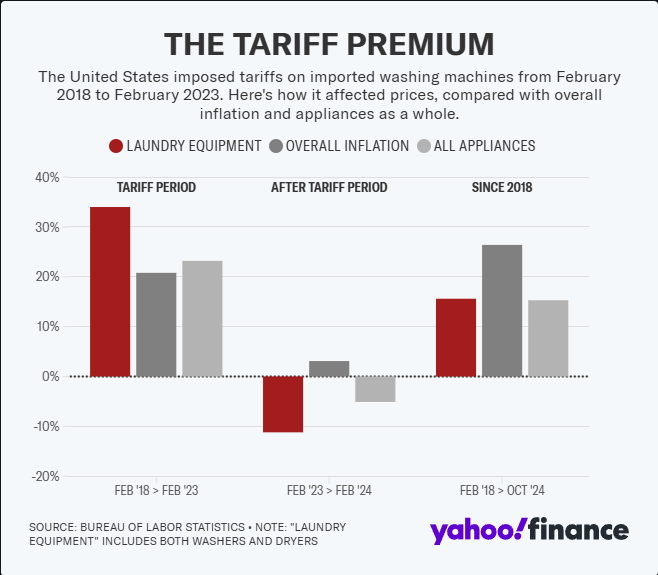

This effect is immediate and measurable. After the 2018 safeguard tariffs on large residential washing machines, prices rose by about 12%, with evidence of substantial pass-through to consumers.[2][3]

A large literature on tariff incidence in the 2018 episode also finds that much of the cost was borne domestically through higher prices, not absorbed by foreign exporters.[4][5]

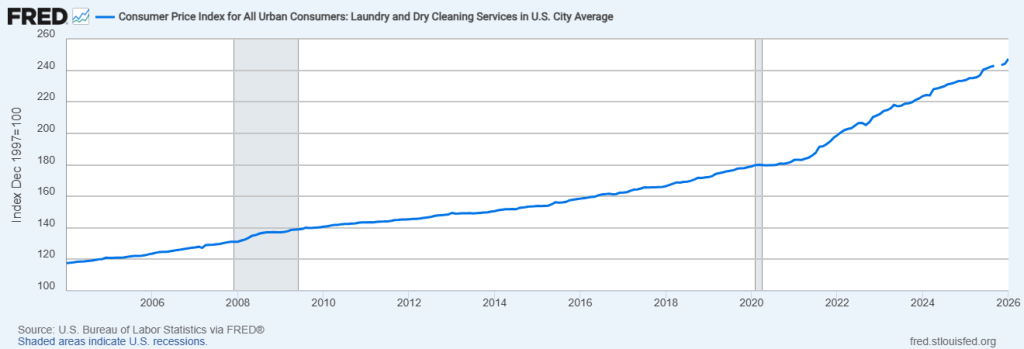

A quick picture of pass-through: laundry-related prices around the 2018 tariffs

One relevant household-adjacent series is CPI for Laundry and Dry Cleaning Services

[[1]](https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/CUSR0000SEGD03)

This is not a washing-machine index, but it provides context for price dynamics in a category adjacent to the 2018 safeguard episode, while the washing-machine price estimate remains sourced to the specific washing-machine tariff analysis.

Retaliatory tariffs hit exporters

Trade wars escalate. When the U.S. imposes tariffs, targeted countries retaliate. China responded to U.S. tariffs by targeting American agricultural exports: soybeans, pork, corn.

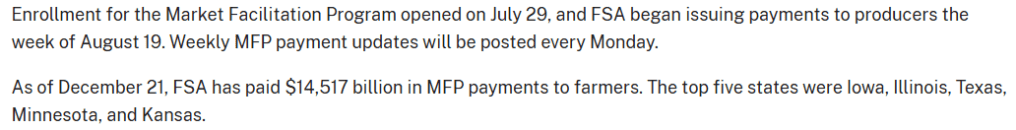

Suddenly, Iowa farmers lost access to one of their largest export markets. Prices fell, inventories rose, and many operations faced severe cash flow pressure. The federal government then spent tens of billions on farm support programs intended to offset trade-related losses, including the Market Facilitation Program (MFP).[6][7]

Trade-war compensation (MFP) shows how retaliation costs get socialized

After retaliation hit U.S. farm exports, the federal government spent tens of billions on support programs like USDA’s Market Facilitation Program (MFP).

[[4]](https://www.farmers.gov/protection-recovery/mfp)

This is the hidden fiscal side of tariffs: even when a tariff is framed as “making foreign exporters pay,” the real-world adjustment often shows up as domestic assistance, deficits, or both.

Long-term business decisions compound the effects

Businesses make investment decisions based on policy expectations. When tariffs create uncertainty, companies delay expansions, relocate production, or cancel projects entirely.

A manufacturer considering building a new factory in Michigan might decide to build in Mexico instead, ensuring access to global supply chains without tariff complications. Once that investment is made, it is difficult to reverse. Temporary tariffs can cause permanent shifts in production locations.

Currency effects amplify disruption

When a country imposes tariffs, exchange rates often adjust. A weaker foreign currency can offset some of the tariff, reducing the intended protection. Meanwhile, a stronger dollar makes U.S. exports more expensive abroad.

This is one reason tariffs often under-deliver on “bring the jobs back” promises. Prices rise at home while competitiveness problems shift rather than disappear.

The part most debates skip: who is allowed to impose tariffs – and why that matters

Before arguing about whether tariffs are a good idea, it helps to understand who can legally pull the lever.

At the constitutional level, Congress holds the power to set import tariffs and regulate foreign commerce.[9] Over time, Congress has delegated limited tariff authorities to the President through specific statutes, largely to allow faster response to trade disputes, negotiations, and time-sensitive shocks.

That delegation is not supposed to be a blank check. Most lanes require a defined justification and a process.

- Congress can raise or lower tariffs directly through legislation.

- The President, acting through delegated authority, can impose certain tariffs when statutory conditions are met (for example, safeguard actions following an investigation and findings).[10]

- Agencies do much of the mechanics: USTR coordinates trade policy and many tariff actions, the ITC provides findings in some lanes, and Customs enforces collection at the border.

This division of authority matters because tariffs are not just economics. They are a form of taxation, a form of industrial policy, and sometimes a tool of foreign policy. When tariffs are imposed broadly outside narrow statutory purposes, the policy can become less predictable, harder to unwind, and more likely to escalate, because it is easier to impose than to repeal.

The part most debates skip: there are better tools than tariffs

Tariffs are a blunt instrument. Sometimes they are used to solve problems they are poorly suited for: job loss in a region, unfair foreign subsidies in a narrow sector, supply chain dependence in strategic goods, or a desire to rebuild domestic capacity.

There are alternatives that are more targeted, more transparent, and often less inflationary than an across-the-board import tax.

1) Help workers and communities directly (adjustment assistance)

If the real problem is disruption, then the cleanest policy response is to support displaced workers rather than taxing every consumer purchase.

Better tools: wage insurance, retraining tied to local employer demand, relocation support, and time-limited income support.

Who benefits vs. who pays

Tariffs concentrate benefits in protected firms while spreading costs across consumers and downstream employers. (A simple Sankey diagram can illustrate this distribution if you want a visual.)

2) Enforce trade rules narrowly (anti-dumping and countervailing duties)

If the issue is dumping or foreign subsidies, a narrow case-based remedy can be a better fit than broad tariffs. These tools aim at the specific products and firms involved instead of taxing whole categories.

3) Use procurement strategically (without taxing everyone)

If the political goal is “tax dollars should build domestic capability,” procurement preferences can concentrate the policy in government purchases rather than raising prices for every household.

4) Build competitiveness by lowering domestic costs (instead of raising import prices)

If the goal is to make domestic production viable, it often makes more sense to reduce domestic frictions:

- faster permitting for factories and infrastructure

- workforce pipelines (apprenticeships and technical training)

- R&D and commercialization support

- logistics improvements (ports, rail, roads)

5) Invest in resilience directly (diversify, stockpile, substitute)

If the fear is a supply shock, tariffs are a clumsy form of insurance.

Better tools: diversified sourcing (“friend-shoring”), stockpiles for truly critical inputs, and R&D for substitutes.

Do tariffs ever make sense? Sometimes. But only in narrow conditions.

Tariffs are not always irrational. The question is whether they are being used for a job they can plausibly do.

Case A: Narrow correction for proven dumping/subsidies

When there is credible evidence of dumping or state subsidy and the policy is tightly scoped, trade remedies can improve fairness without taxing unrelated supply chains.

Case B: National security for truly critical goods

If supply interruption would be catastrophic and substitutes are limited, paying a premium for domestic or diversified capacity can be worthwhile.

The positive outcome here is not “lower prices.” It is reduced vulnerability.

Case C: Temporary breathing room paired with real restructuring

The “infant industry” case can work in theory if protection is:

- time-limited

- conditional on productivity improvements

- paired with investment and modernization

Without that structure, tariffs can become permanent protection that rewards stagnation.

Case D: Negotiation leverage (high-risk, mixed record)

Tariffs can be used as leverage, but the risk is that retaliation and escalation dominate. In practice, “leverage tariffs” work best when goals are clear, allies are aligned, and there is an exit ramp.

What local policymakers should understand

Mayors and city councils sometimes lobby for federal tariffs, hoping to protect local industries. But they should understand:

- Supply chain complexity: protecting one industry can harm several others in the same community.

- Consumer costs: higher prices reduce overall local spending.

- Retaliation risk: exporters become collateral damage.

- Investment uncertainty: firms avoid places where policy creates unpredictable costs.

- Better alternatives: worker support, infrastructure, and targeted industrial policy can help without broad price increases.

Tariffs are a blunt instrument with complex, often counterproductive effects. What appears to help one factory on the edge of town can harm the restaurant downtown, the farm outside city limits, and the families trying to afford groceries.

The bottom line

If the policy goal is resilience, fairness, or industrial renewal, the highest-return move is usually not a broad import tax. It is a targeted package that:

- helps workers and regions adjust,

- enforces trade rules case-by-case,

- uses procurement and industrial policy transparently,

- and invests directly in capacity where national security truly requires it.

Local economies thrive on interconnection. Trade policies that restrict both rarely deliver the promised benefits.

Sources

Price impacts (washing machines)

- Washing machine and dryer prices increased about 12% after the 2018 safeguard tariffs, with evidence of substantial pass-through to consumers.[2]

- A summary write-up of the 12% estimate and underlying research.[3]

- Context series: CPI for Laundry and Dry Cleaning Services (CUSR0000SEGD03).[1]

Who pays for tariffs (tariff incidence)

- Evidence that 2018 tariff costs were largely borne domestically through higher prices, with substantial pass-through.[4]

- Longer-run perspective on who pays for U.S. tariffs (Amiti, Redding, Weinstein).[5]

Downstream employment effects

- Federal Reserve analysis of 2018–2019 tariffs on manufacturing: higher input costs, higher producer prices, and negative net employment effects in affected sectors.[6]

Retaliation and farm support payments

- USDA Market Facilitation Program (MFP) overview and 2018 payment totals (archived program page).[6]

- GAO summary of 2019 MFP payments (about $14.4B in 2019), which supports the scale of the trade-related assistance across years.[7]

One good visualization on varied tariff effects

- Reuters graphic: “Tariffs don’t all act the same” (includes context and visualizations, including laundry equipment notes).[8]

Discover more from The Rational Moderate

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.